Primitivism: Difference between revisions

→Philosophy: c/e npov. |

→Philosophy: c/e |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

== Philosophy == |

== Philosophy == |

||

Primitivism is a [[utopian]] style of art that |

Primitivism is a [[utopian]] style of art that represents the physical world of wild Nature and of humanity in their original [[state of nature]] that existed before civilization, usually represented in two styles (i) ''chronological primitivism'' and (ii) ''cultural primitivism''.<ref name="auto">Lovejoy, A. O. and Boas, George Boas. ''Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity'' (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1935).</ref> In Europe, the ostensible superiority of primitive life was expressed in the myth of a past [[Golden Age|golden age]], as depicted in the [[Pastoral]] genres of European poetry and representational art.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Hamilton|first=Albert Charles|title=The Spenser Encyclopedia|publisher=University of Toronto Press|year=1997|isbn=0-8020-2676-1|location=Toronto|pages=557|language=en}}</ref> |

||

During the [[Age of Enlightenment]], |

During the [[Age of Enlightenment]], intellectuals used the [[idealization]] of indigenous peoples as a rhetorical device to criticize [[European culture]];<ref>Anthony Pagden, “The Savage Critic: Some European Images of the Primitive”, ''The Yearbook of English Studies'', 13 (1983), 32–45.</ref> however, in the field of aesthetics, as part of the [[Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns]], the Italian intellectual [[Giambattista Vico]] (1688–1744) said that the lives of non-European primitive peoples were closer to the inspirational sources of poetry and the arts than was civilized modern man. From that perspective, Vico debated and compared the artistic merits of the [[epic poetry]] of [[Homer]] and of the Bible against the modern literature written in vernacular language in the 18th century.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Bitterli|first=Urs|title=Cultures in Conflict: Encounters Between European and Non-European Cultures, 1492-1800|last2=Robertson|first2=Ritchie|publisher=Stanford University Press|year=1989|isbn=978-0-8047-2176-9|location=Stanford, CA|pages=12}}</ref> |

||

In the 18th century, the |

In the 18th century, the scholar [[Friedrich August Wolf]] identified the language of Homer's poetry and the language of The Bible as examples of folk art communicated and transmitted by [[oral tradition]] (''Prolegomena to Homer'', 1795).<ref>{{Cite book|last=Anttonen|first=Pertti|title=Oral Tradition and Book Culture|last2=Forselles|first2=Cecilia af|last3=Salmi-Niklander|first3=Kirsti|publisher=Finnish Literature Society|year=2018|isbn=978-951-858-007-5|location=Helsinki|pages=70|language=en}}</ref> Vico and Wolf's ideas were developed further at the beginning of the 19th century by [[Johann Gottfried Herder|Herder]].<ref>See Isaiah Berlin, ''Vico and Herder'' (New York: Viking, 1976).</ref> Nevertheless, although influential in literature, such arguments were known to a relatively small number of educated people and their impact was limited or non-existent in the sphere of visual arts.<ref>See [[William Rubin]], "Modernist Primitivism, 1984," p. 320 in ''Primitivism: Twentieth Century Art, A Documentary History'', Jack Flam and Miriam Deutch, editors.</ref> |

||

The 19th century saw for the first time the emergence of [[historicism]], or the ability to judge different eras by their own context and criteria. As a result of this, new schools of visual art arose that aspired to previously unprecedented levels of historical fidelity in setting and costumes. [[Neoclassicism]] in visual art and architecture was one result. Another such "historicist" movement in art was the [[Nazarene movement]] in Germany, which took inspiration from the so-called Italian "primitive" school of devotional paintings (i.e., before the age of [[Raphael]] and the discovery of [[oil painting]]). |

The 19th century saw for the first time the emergence of [[historicism]], or the ability to judge different eras by their own context and criteria. As a result of this, new schools of visual art arose that aspired to previously unprecedented levels of historical fidelity in setting and costumes. [[Neoclassicism]] in visual art and architecture was one result. Another such "historicist" movement in art was the [[Nazarene movement]] in Germany, which took inspiration from the so-called Italian "primitive" school of devotional paintings (i.e., before the age of [[Raphael]] and the discovery of [[oil painting]]). |

||

Revision as of 13:46, 20 January 2023

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2021) |

In the arts of the Western World, Primitivism is a mode of aesthetic idealization that means to recreate the experience of the primitive time, place, and person, either by emulation or by recreation. In Western philosophy, primitivism proposes that the people of a primitive society possess a Morality and an ethics that are superior to the urban value system of civilized people; thus, in art and in philosophy, Primitivism is nostalgia for a non-existent golden age in the Garden of Eden.[1]

In European art, the aesthetics of primitivism included techniques, motifs, and styles copied from the arts of Asian, African, and Australasian peoples perceived as primitive in relation to the urban civilization of western Europe. In that light, the painter Paul Gauguin's inclusion of Tahitian imagery to his oil paintings was a characteristic borrowing of technique, motif, and style that was important to the development of Modern art (1860s–1970s) in the late 19th century.[2] As a genre of Western art, Primitivism reproduced and perpetuated racist stereotypes, such as “The Noble Savage”, with which colonialists justified white colonial rule over the non-white Other in Asia, Africa, and Australasia.[3]

Moreover, the term primitivism also identifies the techniques, motifs, and styles of painting that predominated representational painting before the emergence of the Avant-garde; and also identifies the styles of Naïve art and of folk art produced by amateur artists, such as Henri Rousseau, who painted for personal pleasure.[4]

Philosophy

Primitivism is a utopian style of art that represents the physical world of wild Nature and of humanity in their original state of nature that existed before civilization, usually represented in two styles (i) chronological primitivism and (ii) cultural primitivism.[5] In Europe, the ostensible superiority of primitive life was expressed in the myth of a past golden age, as depicted in the Pastoral genres of European poetry and representational art.[6]

During the Age of Enlightenment, intellectuals used the idealization of indigenous peoples as a rhetorical device to criticize European culture;[7] however, in the field of aesthetics, as part of the Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, the Italian intellectual Giambattista Vico (1688–1744) said that the lives of non-European primitive peoples were closer to the inspirational sources of poetry and the arts than was civilized modern man. From that perspective, Vico debated and compared the artistic merits of the epic poetry of Homer and of the Bible against the modern literature written in vernacular language in the 18th century.[8]

In the 18th century, the scholar Friedrich August Wolf identified the language of Homer's poetry and the language of The Bible as examples of folk art communicated and transmitted by oral tradition (Prolegomena to Homer, 1795).[9] Vico and Wolf's ideas were developed further at the beginning of the 19th century by Herder.[10] Nevertheless, although influential in literature, such arguments were known to a relatively small number of educated people and their impact was limited or non-existent in the sphere of visual arts.[11]

The 19th century saw for the first time the emergence of historicism, or the ability to judge different eras by their own context and criteria. As a result of this, new schools of visual art arose that aspired to previously unprecedented levels of historical fidelity in setting and costumes. Neoclassicism in visual art and architecture was one result. Another such "historicist" movement in art was the Nazarene movement in Germany, which took inspiration from the so-called Italian "primitive" school of devotional paintings (i.e., before the age of Raphael and the discovery of oil painting).

Where conventional academic painting (after Raphael) used dark glazes, highly selective, idealized forms, and rigorous suppression of details, the Nazarenes used clear outlines, bright colors, and paid meticulous attention to detail. The school's artistic styles were similar in nature to the Pre-Raphaelites, who were primarily inspired by the critical writings of John Ruskin, who admired the painters before Raphael (such as Botticelli) and who also recommended painting outdoors, a practice then unheard of.

Two developments shook the world of visual art in the mid-19th century. The first was the invention of the photographic camera, which arguably spurred the development of Realism in art. The second was a discovery in the world of mathematics of non-Euclidean geometry, which overthrew the 2000-year-old seeming absolutes of Euclidean geometry and threw into question conventional Renaissance perspective by suggesting the possible existence of multiple dimensional worlds and perspectives in which things might look very different.[12]

The discovery of possible new dimensions had the opposite effect of photography and worked to counteract realism. Artists, mathematicians, and intellectuals now realized that there were other ways of seeing things beyond what they had been taught in Beaux Arts schools of Academic painting, which prescribed a rigid curriculum based on the copying of idealized classical forms and held up Renaissance perspective painting as the culmination of civilization and knowledge.[13] Beaux Arts academies held onto the idea that non-Western peoples had no art or only inferior art.

In rebellion against this dogmatic approach, Western artists began to try to depict realities that might exist in a world beyond the limitations of the three-dimensional world of conventional representation mediated by classical sculpture. They looked to Japanese and Chinese art, which they regarded as learned and sophisticated, and did not employ Renaissance one-point perspective. Non-Euclidean perspective and tribal art fascinated Western artists who saw in them the still-enchanted portrayal of the spirit world. They also looked to the art of untrained painters and to children's art, which they believed depicted interior emotional realities that had been ignored in conventional, cookbook-style academic painting.

Tribal and other non-European art also appealed to those who were unhappy with the repressive aspects of European culture, as pastoral art had done for millennia.[14] Imitations of tribal or archaic art also fall into the category of nineteenth-century "historicism", as these imitations strive to reproduce this art in an authentic manner. Actual examples of tribal, archaic, and folk art were prized by both creative artists and collectors.

The painting of Paul Gauguin and Pablo Picasso and the music of Igor Stravinsky is frequently cited as the most prominent examples of primitivism in art. Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring is "primitivist" insofar as its programmatic subject is a pagan rite: a human sacrifice in pre-Christian Russia. It employs harsh dissonance and loud, repetitive rhythms to depict "Dionysian" modernism, i.e., abandonment of inhibition (restraint standing for civilization). Nevertheless, Stravinsky was a master of learned classical tradition and worked within its bounds. According to Malcolm Cook, “with its folk-music motifs and the infamous 1913 Paris riot securing its avant-garde credentials, Stravinsky's Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913) engaged in primitivism in both form and practice while remaining embedded within Western classical practices.”[15] In his later work, he adopted a more "Apollonian" neoclassicism, to use Nietzsche's terminology, although in his use of serialism he still rejects 19th-century convention. In modern visual art, Picasso's work is also understood as rejecting Beaux Arts' artistic expectations and expressing primal impulses, whether he worked in a cubist, neo-classical, or tribal-art-influenced vein.

Origins of modernist primitivism

Primitivism gained momentum from anxieties about technological innovation but above all from the "Age of Discovery", which introduced the West to previously unknown peoples and opened the doors to colonialism.[16] During the European Enlightenment, with the decline of feudalism, philosophers started questioning many fixed medieval assumptions about human nature, the position of humans in society, and the strictures of Christianity, and especially Catholicism.[17] They began questioning the nature of humanity and its origins through a discussion of the natural man, which had intrigued theologians since the European encounter with the New World.

From the 18th century, Western thinkers and artists continued to engage in the retrospective tradition, that is "the conscious search in history for a more deeply expressive, permanent human nature and cultural structure in contrast to the nascent modern realities".[18] Their search led them to parts of the world that they believed constituted alternatives to modern civilization.

The invention of the steamboat and other innovations in global transportation in the 19th century brought the indigenous cultures of the European colonies and their artifacts' into the metropolitan centers of the empire. Many Western-trained artists and connoisseurs were fascinated by these objects, attributing their features and styles to "primitive" forms of expression; especially the perceived absence of linear perspective, simple outlines, the presence of symbolic signs such as the hieroglyph, emotive distortions of the figure, and the perceived energetic rhythms resulting from the use of repetitive ornamental pattern.[19] According to recent cultural critics, it was primarily the cultures of Africa and the Oceanic islands that provided artists an answer to what these critics call their "white, Western, and preponderantly male quest" for the "elusive ideal" of the primitive, "whose very condition of desirability resides in some form of distance and difference."[20] These energizing stylistic attributes, present in the visual arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Indians of the Americas, could also be found in the archaic and peasant art of Europe and Asia, as well.

Paul Gauguin

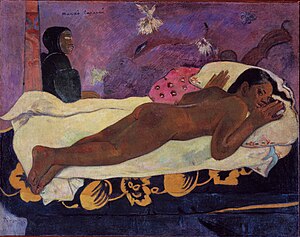

Painter Paul Gauguin left the technologic society of Europe to reside in the French colony of Tahiti, where he adopted a primitive style of life unlike that of urban France. Gauguin's search for the primitive was a search for sexual freedom from the Christian constrictions of private life in France; evident in the paintings Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892), Parau na te Varua ino (1892), and Anna the Javanerin (1893), Te Tamari No Atua (1896) and Cruel Tales (1902). Gauguin's view of Tahiti as a sexual utopia free of the complications ingrained in the urban West is in line with the perspective of pastoral art, which idealises rural life as better than city life. Similarities between Pastoralism and Primitivism are evident in the Gauguin paintings Tahitian Pastoral and Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897–1898).[21]

Gauguin said that his work celebrated Tahitian society, and that, as such, he was defending Tahiti against European colonialism; nonetheless, from the postcolonial perspective, feminist art critics said that Gauguin's taking adolescent mistresses voids his anti-colonialist claim.[22] Like the European men of his time, Gauguin saw sexual freedom exclusively from the perspective of the male gaze of the colonizer, because Gauguin's artistic primitivism includes the "dense interweave of racial and sexual fantasies and power, both colonial and patriarchal" created by the French about the Tahitians,[23] which fantasies are "an effort to essentialize notions of primitiveness" by Othering the non-European peoples into subordinate peoples.

Fauves and Pablo Picasso

In 1905–06, a small group of artists began to study art from Sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania, in part because of the compelling works of Paul Gauguin that were gaining visibility in Paris[citation needed]. Gauguin's powerful posthumous retrospective exhibitions at the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1903 and an even larger one in 1906 exerted a strong influence. Artists including Maurice de Vlaminck, André Derain, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso grew increasingly intrigued and inspired by the select objects they encountered.

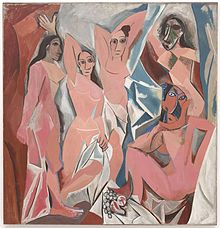

Pablo Picasso, in particular, explored Iberian sculpture, African sculpture, African traditional masks, and other historical works including the Mannerist paintings of El Greco, resulting in his masterpiece Les Demoiselles D'Avignon and, eventually, the invention of Cubism.[24]

The generalizing term "primitivism" tends to obscure the distinct contributions to modern art from these various visual traditions.[25]

Anti-colonial primitivism

Although primitivism in art is usually regarded as a Western phenomenon, the structure of primitivist idealism can be found in the work of non-Western and specifically anti-colonial artists. The desire to recover a notional and idealized past when humans had been one with nature is connected to the critique of the impact of Western modernity on colonized societies. These artists often critique Western stereotypes about "primitive" colonized peoples while at the same time yearning to recover pre-colonial modes of experience. Anticolonialism fuses with primitivism's reverse teleology to produce art that is distinct from the primitivism of Western artists which usually reinforces rather than critiques colonial stereotypes.[26]

The work of artists connected with the Négritude movement in particular demonstrates this tendency. Négritude was a movement of neo-African idealism and political agitation that was begun by francophone intellectuals and artists on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1930s, and which spread across Africa and the African diaspora in subsequent years. They self-consciously idealized pre-colonial Africa, something that took many forms. This typically consisted in rejecting overweening European rationalism and the associated ravages of colonialism while positing pre-colonial African societies as having had a more communal and organic basis. The work of the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam is particularly notable among the visual artists of Négritude. Lam met Pablo Picasso and the European surrealists while living in Paris in the 1930s.[27] When he returned to Cuba in 1941, Lam was emboldened to create images in which humans, animals, and nature combined in lush and dynamic tableaux. In his iconic work of 1943, The Jungle, Lam's characteristic polymorphism recreates a fantastical jungle scene with African motifs between stalks of cane. It vividly captures the way in which Négritude's neo-African idealism is connected to a history of plantation slavery centered on the production of sugar.

Neo-primitivism

Neo-primitivism was a Russian art movement that took its name from the 31-page pamphlet Neo-primitivizm, by Aleksandr Shevchenko (1913). It is considered a type of avant-garde movement and is proposed as a new style of modern painting which fuses elements of Cézanne, Cubism, and Futurism with traditional Russian 'folk art' conventions and motifs, notably the Russian icon and the lubok.

Neo-primitivism replaced the symbolist art of the Blue Rose movement. The nascent movement was embraced due to its predecessor's tendency to look back so that it passed its creative zenith.[28] A conceptualization of neo-primitivism describes it as anti-primitivist Primitivism since it questions the primitivist's Eurocentric universalism.[29] This view presents neo-primitivism as a contemporary version that repudiates previous primitivist discourses.[29] Some characteristics of neo-primitivist art include the use of bold colors, original designs, and expressiveness.[30] These are demonstrated in the works of Paul Gauguin, which feature vivid hues and flat forms instead of a three-dimensional perspective.[31] Igor Stravinsky was another neo-primitivist known for his children's pieces, which were based on Russian folklore.[32] Several neo-primitivist artists were also previous members of the Blue Rose group.[33]

Neo-primitive artists

Russian artists associated with Neo-primitivism include:

- David Burlyuk

- Marc Chagall

- Pavel Filonov

- Natalia Goncharova

- Mikhail Larionov

- Kasimir Malevich

- Aleksandr Shevchenko

- Igor Stravinsky

Museum exhibitions on primitivism in modern art

In November 1910, Roger Fry organized the exhibition titled Manet and the Post-Impressionists held at the Grafton Galleries in London. This exhibition showcased works by Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Édouard Manet, Pablo Picasso, and Vincent Van Gogh, among others. This exhibition was meant to showcase how French art had developed over the past three decades; however, art critics in London were shocked by what they saw. Some called Fry “mad” and “crazy” for publicly displaying such artwork in the exhibition.[34] Fry's exhibition called attention to primitivism in modern art even if he did not intend for it to happen; leading American scholar Marianna Torgovnick to term the exhibition as the "debut" of primitivism on the London art scene.[35]

In 1984, The Museum of Modern Art in New York had a new exhibition focusing on primitivism in modern art. Instead of pointing out the obvious issues, the exhibition celebrated the use of non-Western objects as inspiration for modern artists. The director of the exhibition, William Rubin, took Roger Fry's exhibition one step further by displaying the modern works of art juxtaposed to the non-Western objects themselves. Rubin stated, “That he was not so much interested in the pieces of ‘tribal’ art in themselves but instead wanted to focus on the ways in which modern artists ‘discovered’ this art.”[36] He was trying to show there was an ‘affinity’ between the two types of art. Scholar Jean-Hubert Martin argued this attitude effectively meant that the ‘tribal’ art objects were “given the status of not much more than footnotes or addenda to the Modernist avant-garde.”[37] Rubin's exhibition was divided into four different parts: Concepts, History, Affinities, and Contemporary Explorations. Each section is meant to serve a different purpose in showing the connections between modern art and non-Western ‘art.’

In 2017, the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in collaboration with the Musée National Picasso – Paris, put on the exhibition Picasso Primitif. Yves Le Fur, the director, stated he wanted this exhibition to invite a dialogue between “the works of Picasso – not only the major works but also the experiments with aesthetic concepts – with those, no less rich, by non-Western artists."[38] Picasso Primitif meant to offer a comparative view of the artist's works with those of non-Western artists. The resulting confrontation was supposed to reveal the similar issues those artists have had to address such as nudity, sexuality, impulses and loss through parallel plastic solutions.

In 2018, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts had an exhibition titled From Africa to the Americas: Face-to-Face Picasso, Past and Present. The MMFA adapted and expanded on Picasso Primitif by bringing in 300 works and documents from the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac and the Musée National Picasso – Paris. Nathalie Bondil saw the issues with the ways in which Yves Le Fur presented Picasso's work juxtaposed to non-Western art and objects and found a way to respond to it. The headline of this exhibition was, “A major exhibition offering a new perspective and inspiring a rereading of art history.”[39] The exhibition looked at the transformation in our view of the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas from the end of the 19th century to the present day. Bondil wanted to explore the question about how ethnographic objects come to be viewed as art. She also asked, “How can a Picasso and an anonymous mask be exhibited in the same plane?”[40]

See also

Notes

- ^ Hirsch, Edward (2014). A Poet's Glossary. New York: HMH. p. 485. ISBN 978-0-15-101195-7.

- ^ Atkins, Robert. Artspoke (1993) ISBN 978-1-55859-388-6

- ^ See: Marianna Torgovnick. Gone primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991); Ben Etherington, Literary Primitivism (Stanford: Stanford UP, 2018).

- ^ Camayd-Freixas, Erik; Gonzalez, Jose Eduardo (2000). Primitivism and Identity in Latin America: Essays on Art, Literature, and Culture. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8165-2045-9.

- ^ Lovejoy, A. O. and Boas, George Boas. Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1935).

- ^ Hamilton, Albert Charles (1997). The Spenser Encyclopedia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 557. ISBN 0-8020-2676-1.

- ^ Anthony Pagden, “The Savage Critic: Some European Images of the Primitive”, The Yearbook of English Studies, 13 (1983), 32–45.

- ^ Bitterli, Urs; Robertson, Ritchie (1989). Cultures in Conflict: Encounters Between European and Non-European Cultures, 1492-1800. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8047-2176-9.

- ^ Anttonen, Pertti; Forselles, Cecilia af; Salmi-Niklander, Kirsti (2018). Oral Tradition and Book Culture. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. p. 70. ISBN 978-951-858-007-5.

- ^ See Isaiah Berlin, Vico and Herder (New York: Viking, 1976).

- ^ See William Rubin, "Modernist Primitivism, 1984," p. 320 in Primitivism: Twentieth Century Art, A Documentary History, Jack Flam and Miriam Deutch, editors.

- ^ See Linda Dalrymple Henderson, The Fourth Dimension and non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art (Princeton University Press, 19810).

- ^ Natasha. "Ecole des Beaux-Arts". www.jssgallery.org. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Connelly, F, The Sleep of Reason, (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), p.5.

- ^ Cook, Malcolm (2017-08-24). "A Primitivism of the Senses". In Rogers, Holly; Barham, Jeremy (eds.). The Music and Sound of Experimental Film. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190469894.003.0003.

- ^ Diamond, S: In Search of the Primitive, (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1974), pp. 215-217.

- ^ Diamond, Stanley (2017). In Search of the Primitive: A Critique of Civilization. Oxon: Taylor & Francis. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-138-08779-8.

- ^ Diamond 1974, p. 215.

- ^ Robert Goldwater, Primitivism in Modern Art, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage, 1967).

- ^ See Solomon-Godeau 1986, p. 314.

- ^ About the painting Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897–1898), the art historian George T.M. Shackelford said: "Although, [Gauguin] downplayed the painting's relationship to the murals of Puvis, on the grounds of procedure and intention, in formal terms he cannot have hoped that his figured landscape — for all its apparent rejection of classical formulas and execution — could escape comparison with the timeless groves that Puvis had popularized in murals for the museums in Lyon and Rouen, as well as the great hemicycle of the Sorbonne."

- ^ Solomon-Godeau 1986, p.324.

- ^ Solomon-Godeau 1986, p.315.

- ^ Cooper, 24

- ^ Cohen, Joshua I. “Fauve Masks: Rethinking Modern 'Primitivist' Uses of African and Oceanic Art, 1905-8.” The Art Bulletin 99, no. 2 (June 2017): 136-65.

- ^ See Ben Etherington, Literary Primitivism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018).

- ^ Lowery Stokes Sims. Wifredo Lam and the international avant-garde, 1923-1982. University of Texas Press, 2002.

- ^ Bowlt, John E. (1976). Russian Art, 1875-1975: A Collection of Essays. New York, NY: MSS Information Corporation. p. 94. ISBN 0-8422-5262-2.

- ^ a b Li, Victor (2006). The Neo-primitivist Turn: Critical Reflections on Alterity, Culture, and Modernity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. ix, 18, 19. ISBN 0-8020-9111-3.

- ^ Bachus, Nancy; Glover, Daniel (2006). The Modern Piano: The Influence of Society, Style, and Musical Trends on the Great Piano Composers. Los Angeles, CA: Alfred Music Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 0-7390-4298-X.

- ^ Bachus, Nancy; Glover, Daniel (2003). Beyond the Romantic Spirit 1880-1922. Los Angeles, CA: Alfred Music Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7390-3217-6.

- ^ Foxcroft, Nigel H. (2019). The Kaleidoscopic Vision of Malcolm Lowry: Souls and Shamans. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4985-1657-0.

- ^ Brooker, Peter; Thacker, Andrew (2013). The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, Volume III. Oxon: Oxford University Press. p. 1289. ISBN 978-0-19-968130-3.

- ^ Frances Spalding, “Roger Fry and His Critics in a Post-Modernist Age,” The Burlington Magazine 128, no. 1000 (1986): 490.

- ^ Marianna Torgovnick, Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives, Nachdr. (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1990), 104.

- ^ William Rubin et al., eds., “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (New York : Boston: Museum of Modern Art ; Distributed by New York Graphic Society Books, 1984).

- ^ Jean-Hubert Martin, The Whole Earth Show, interview by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, July 1989.

- ^ Yves Le Fur, “Picasso Primitif,” Exhibition Leaflet, Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, 2017, 2.

- ^ “From Africa to the Americas: Face-to-Face Picasso, Past and Present,” The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, accessed December 3, 2018.

- ^ Ian McGillis, “MMFA Show Shines a Light on How Picasso Tapped into Africa to Redefine Art in the 20th Century,” Montreal Gazette, May 4, 2018.

References

- Antliff, Mark and Patricia Leighten, "Primitive" in Critical Terms for Art History, R. Nelson and R. Shiff (Eds.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996 (rev. ed. 2003).

- Blunt, Anthony & Pool, Phoebe. Picasso, the Formative Years: A Study of His Sources. Graphic Society, 1962.

- Connelly, S. Frances. The Sleep of Reason: Primitivism in Modern European Art and Aesthetics, 1725-1907. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999.

- del Valle, Alejandro. (2015). "Primitivism in the Art of Ana Mendieta". Tesis doctoral. Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- Cooper, Douglas The Cubist Epoch, Phaidon in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art & the Metropolitan Museum of Art, London, 1970, ISBN 0-87587-041-4

- Diamond, Stanley. In Search of the Primitive: A Critique of Civilization. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1974.

- Etherington, Ben. Literary Primitivism. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018.

- Flam, Jack and Miriam Deutch, eds. Primitivism and Twentieth-Century Art Documentary History. University of California Press, 2003.

- Goldwater, Robert. Primitivism in Modern Art. Belnap Press. 2002.

- Lovejoy, A. O. and George Boas. Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1935 (With supplementary essays by W. F. Albright and P. E. Dumont, Baltimore and London, Johns Hopkins U. Press. 1997).

- Redfield, Robert. "Art and Icon" in Anthropology and Art, C. Otten (Ed.). New York: Natural History Press, 1971.

- Rhodes, Colin. Primitivism and Modern Art. London: Thames and Hudson, 1994.

- Shevchenko, Aleksandr. 1913. Neo-primitivizm: ego teoriia, ego vozmozhnosti, ego dostizheniia. Moscow: [s.n.].

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. "Going Native: Paul Gauguin and the Invention of Primitivist Modernism" in The Expanded Discourse: Feminism and Art History, N. Broude and M. Garrard (Eds.). New York: Harper Collins, 1986.

External links

- John Zerzan, Telos 124, Why Primitivism?. New York: Telos Press Ltd., Summer 2002. (Telos Press).

- Articles on Primitivism

- "Primitivism meaning and methods""Primitivism, or anarcho-primitivism, is an anarchist critique of the origins and progress of civilization. Primitivists argue that the shift from hunter-gatherer to agricultural subsistence gave rise to social stratification, coercion, and alienation. "

- Research Group in Primitive Art and Primitivism (CIAP-UPF)

- Ben Etherington, "The New Primitives", Los Angeles Review of Books, May 24, 2018.

Further reading on Neo-primitivism

- Cowell, Henry. 1933. "Towards Neo-Primitivism". Modern Music 10, no. 3 (March–April): 149–53. Reprinted in Essential Cowell: Selected writings on Music by Henry Cowell, 1921–1964, edited by Richard Carter (Dick) Higgins and Bruce McPherson, with a preface by Kyle Gann, 299–303. Kingston, NY: Documentext, 2002. ISBN 978-0-929701-63-9.

- Doherty, Allison. 1983. "Neo-Primitivism". MFA diss. Syracuse: Syracuse University.

- Floirat, Anetta. 2015a. "Chagall and Stravinsky: Parallels Between a Painter and a Musician Convergence of Interests", Academia.edu (April).

- Floirat, Anetta. 2015b. "Chagall and Stravinsky, Different Arts and Similar Solutions to Twentieth-Century Challenges". Academia.edu (April).

- Floirat, Anetta. 2016. "The Scythian Element of the Russian Primitivism, in Music and Visual arts. Based on the Work of Three Painters (Goncharova, Malevich and Roerich) and Two Composers (Stravinsky and Prokofiev)". Academia.edu.

- Garafola, Lynn. 1989. "The Making of Ballet Modernism". Dance Research Journal 20, no. 2 (Winter: Russian Issue): 23–32.

- Hicken, Adrian. 1995. "The Quest for Authenticity: Folkloric Iconography and Jewish Revivalism in Early Orphic Art of Marc Chagall (c. 1909–1914)". In Fourth International Symposium Folklore–Music–Work of Art, edited by Sonja Marinković and Mirjana Veselinović-Hofman, 47–66. Belgrade: Fakultet Muzičke Umetnosti.

- Nemirovskaâ, Izol'da Abramovna [Немировская, Изольда Абрамовна]. 2011. "Музыка для детей И.Стравинского в контексте художественной культуры рубежа XIX-ХХ веков" [Stravinsky's Music for Children and Art Culture at the Turn of the Twentieth Century]. In Вопросы музыкознания: Теория, история, методика. IV [Problems in Musicology: Theory, History, Methodology. IV], edited by Ûrij Nikolaevic Byckov [Юрий Николаевич Бычков] and Izol'da Abramovna Nemirovskaâ [Изольда Абрамовна Немировская], 37–51. Moscow: Gosudarstvennyj Institut Muzyki im. A.G. Snitke. ISBN 978-5-98079-720-1.

- Sharp, Jane Ashton. 1992. "Primitivism, 'Neoprimitivism', and the Art of Natal'ia Gonchrova, 1907–1914". Ph.D. diss. New Haven: Yale University.