Stefan the First-Crowned: Difference between revisions

Norden1990 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

m date format audit, minor formatting, typo(s) fixed: newly- → newly |

||

| (27 intermediate revisions by 19 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|King of Serbia from 1217 to 1228}} |

{{Short description|King of Serbia from 1217 to 1228}} |

||

{{Hatnote|Not to be confused with Grand Prince [[Stefan Nemanja]], his father.}} |

{{Hatnote|Not to be confused with Grand Prince [[Stefan Nemanja]], his father.}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2024}} |

||

{{Infobox Saint |

{{Infobox Saint |

||

| honorific-prefix = [[Saint]] |

| honorific-prefix = [[Saint]] |

||

| name={{lang|sr-Cyrl|Stefan |

| name={{lang|sr-Cyrl|Stefan Nemanjić}}<br>{{small|{{lang|sr|Стефан Немањић}}}} |

||

| image = Stefan the First-Crowned, fresco from Mileševa.jpg |

| image = Stefan the First-Crowned, fresco from Mileševa.jpg |

||

| image_size = 200px |

| image_size = 200px |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| misc = {{Infobox royalty|embed=yes |

| misc = {{Infobox royalty|embed=yes |

||

| succession = [[Grand Prince of Serbia]] |

| succession = [[Grand Prince of Serbia]] |

||

| religion = [[Serbian Orthodox]] |

| religion = [[Serbian Orthodox Christian]] |

||

| reign = 1196–1228 |

| reign = 1196–1228 |

||

| coronation = 1217 (as king) |

| coronation = 1217 (as king) |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

| successor2 = |

| successor2 = |

||

| spouse = [[Eudokia Angelina]]<br>[[Anna Dandolo]] |

| spouse = [[Eudokia Angelina]]<br>[[Anna Dandolo]] |

||

| issue = [[Stefan Radoslav]]<br>[[Stefan Vladislav]]<br>[[Stefan Uroš I]]<br>[[Sava II]] |

| issue = [[Stefan Radoslav]]<br>[[Stefan Vladislav]]<br>[[Stefan Uroš I]]<br>[[Sava II]]<br/>[[Komnena Nemanjić|Komnena, Grand Duchess of Croia]] |

||

| house = [[Nemanjić dynasty]] |

| house = [[Nemanjić dynasty]] |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

| place of burial = [[Studenica monastery]] |

| place of burial = [[Studenica monastery]] |

||

}}}} |

}}}} |

||

'''Stefan |

'''Stefan Nemanjić''' ({{lang-sr-Cyrl|Стефан Немањић}}, {{IPA-sh|stêfaːn němaɲitɕ|pron}}), known as '''Stefan the First-Crowned''' ({{lang-sr|Стефан Првовенчани|Stefan Prvovenčani}}, {{IPA-sh|stêfaːn prʋoʋěntʃaːniː|pron}}; {{circa|1165}} – 24 September 1228), was the [[Grand Prince of Serbia]] from 1196 and the [[King of Serbia]] from 1217 until his death in 1228. He was the first [[Grand Principality of Serbia|Serbian]] king by [[Nemanjić dynasty]];{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=38–56}}{{sfn|Ćirković|2004|p=33–38}}{{sfn|Curta|2006|p=389–394}}{{sfn|Curta|2019|p=662–664}} due to his transformation of the [[Serbian Grand Principality]] into the [[Kingdom of Serbia (medieval)|Kingdom of Serbia]] and the assistance he provided his brother [[Saint Sava]] in establishing the [[Serbian Orthodox Church]]. |

||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

| Line 54: | Line 55: | ||

In 1196, at the state assembly near [[Church of Saint Apostles Peter and Paul (Novi Pazar)|Church of Saints Peter and Paul]], Stefan Nemanja abdicated the throne in favor of his middle son Stefan, who became the grand zoupan of Serbia. He left his eldest son Vukan in charge of Zeta, Travunija, Hvosno and Toplica. Nemanja became a monk in his old age and was given the name Simeon. Shortly afterwards, he went to Byzantium, to [[Mount Athos]], where his youngest son Sava had been a monk for some time. They received permission from the Byzantine emperor to rebuild the abandoned [[Hilandar|Hilandar monastery]]. |

In 1196, at the state assembly near [[Church of Saint Apostles Peter and Paul (Novi Pazar)|Church of Saints Peter and Paul]], Stefan Nemanja abdicated the throne in favor of his middle son Stefan, who became the grand zoupan of Serbia. He left his eldest son Vukan in charge of Zeta, Travunija, Hvosno and Toplica. Nemanja became a monk in his old age and was given the name Simeon. Shortly afterwards, he went to Byzantium, to [[Mount Athos]], where his youngest son Sava had been a monk for some time. They received permission from the Byzantine emperor to rebuild the abandoned [[Hilandar|Hilandar monastery]]. |

||

[[File:Prvovencani Simon Sopocani.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Stefan Nemanjić as monk Simon. Painted in the endowment of his son [[Stefan Uroš I|Uroš I]] in [[Sopoćani]] c. 1260.]] |

[[File:Prvovencani Simon Sopocani.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Stefan Nemanjić as monk Simon. Painted in the endowment of his son [[Stefan Uroš I|Uroš I]] in [[Sopoćani]] c. 1260.]] |

||

The new [[Pope Innocent III]], who in a letter in 1198 called on the entire West to liberate the [[Holy Land]], was not satisfied with the fact that the Serbs were subordinated to the [[Patriarch of Constantinople]], but wanted to return them to [[Rome]] through Vukan. In 1198, the Hungarian dux |

The new [[Pope Innocent III]], who in a letter in 1198 called on the entire West to liberate the [[Holy Land]], was not satisfied with the fact that the Serbs were subordinated to the [[Patriarch of Constantinople]], but wanted to return them to [[Rome]] through Vukan. In 1198, the Hungarian dux [[Andrew II of Hungary|Andrew]] conquered [[Principality of Hum|Hum (Hercegovina)]] of grand zoupan Stefan and [[Brothers' Quarrel (Hungary)|rebelled]] against brother king [[Emeric of Hungary|Emeric]] but did not gain legitimacy from Rome. In any case, the Hungarians became dominant on the eastern [[Adriatic]] coast. But [[Venice]], because of its business interests, did not like the eastern coast of the Adriatic to be controlled by the mighty Byzantium or Hungary. Vukan and the Hungarian king Emeric (1196–1204) make an alliance against Stefan, after which a civil war breaks out in Serbia. The action against Stefan was preceded by his letter to the Pope in which he asked for the crown. Around 1200, Stefan expelled his wife Eudokia, a daughter of [[Alexios III Angelos]], who found refuge with Vukan in Zeta. Emeric saw Stefan's move as an open attack on his crown, because in Hungary it was traditionally believed that only it in the region could have primacy with the Roman pope. Stefan lost the conflicts and had to flee the country in 1202 to the ruler of [[Second Bulgarian Empire|Bulgaria]] [[Kaloyan of Bulgaria|Kaloyan]].{{sfn|Curta|2006|p=381}}{{sfn|Sweeney|1973|pp=323–324}}{{sfn|Madgearu|2016|p=133}} |

||

In the meantime, control of the newly formed crusade army was taken over by the powerful Venetian doge [[Enrico Dandolo]], who, to the surprise of all, including the pope himself, in the [[Fourth Crusade]] first sent an [[Siege of Zara|attack on Hungarian Zara]] in 1202, and then on Byzantium, whose capital [[Sack of Constantinople|Constantinople crusaders conquered]] in April 1204. Stefan uses this situation and in the counter-offensive, with the help of Prince Kaloyan, he returns to the throne in Ras in 1204, while Vukan retreats to Zeta. The fighting between the brothers was stopped in 1205 and relations were established as they were before the outbreak of the conflict. Meanwhile, in November 1204, the Hungarian king Emeric died and the Kaloyan of Bulgaria was crowned for king by the Pope. |

In the meantime, control of the newly formed crusade army was taken over by the powerful Venetian doge [[Enrico Dandolo]], who, to the surprise of all, including the pope himself, in the [[Fourth Crusade]] first sent an [[Siege of Zara|attack on Hungarian Zara]] in 1202, and then on Byzantium, whose capital [[Sack of Constantinople|Constantinople crusaders conquered]] in April 1204. Stefan uses this situation and in the counter-offensive, with the help of Prince Kaloyan, he returns to the throne in Ras in 1204, while Vukan retreats to Zeta. The fighting between the brothers was stopped in 1205 and relations were established as they were before the outbreak of the conflict. Meanwhile, in November 1204, the Hungarian king Emeric died and the Kaloyan of Bulgaria was crowned for king by the Pope. |

||

Numerous states were created on the ruins of Byzantium, which were almost equal in strength. The Crusaders founded the [[Kingdom of Thessalonica]], the [[principality of Achaia]], the [[duchy of Athens]] and Thebes, the duchy of Archipelago or [[Duchy of Naxos|Naxos]]. They were all under rule of Latin emperor of Constantinople. The remaining Byzantine factions also formed their own successor states on the fringes of the empire, at [[Empire of Nicea|Niceae]] and [[Empire of Trebizond|Trebizond]] in [[Asia Minor]], and at [[Despotate of Epiros|Epiros]] in west Balkan. Of the newly |

Numerous states were created on the ruins of Byzantium, which were almost equal in strength. The Crusaders founded the [[Kingdom of Thessalonica]], the [[principality of Achaia]], the [[duchy of Athens]] and Thebes, the duchy of Archipelago or [[Duchy of Naxos|Naxos]]. They were all under rule of Latin emperor of Constantinople. The remaining Byzantine factions also formed their own successor states on the fringes of the empire, at [[Empire of Nicea|Niceae]] and [[Empire of Trebizond|Trebizond]] in [[Asia Minor]], and at [[Despotate of Epiros|Epiros]] in west Balkan. Of the newly created Greek states, two gained some stability and survived through this period: Niceae under the Laskaris dynasty, which soon became an empire (1208), and Epiros, which took considerably to rise to same status (1224–27). The two rivals sought to present themselves as lawful successor of Empire of the Romans and to get the upper hand in the struggle for its restoration. Bulgaria was located to the north, and Serbia to the northwest. Serbia's neighbors at the time were Epirus to the south, Bulgaria to the east, and the Hungary to the north and west. |

||

==Later rule== |

==Later rule== |

||

| Line 66: | Line 67: | ||

[[File:Reževići Monastery 2a.png|thumb|150px|left|[[Reževići Monastery]] near [[Budva]] was founded by Stefan]] |

[[File:Reževići Monastery 2a.png|thumb|150px|left|[[Reževići Monastery]] near [[Budva]] was founded by Stefan]] |

||

[[Andrija Mirosavljević]] was entitled to the governance of Hum, as the heir of [[Miroslav of Hum]], the uncle of Stefan II, but the Hum nobles chose his brother [[Petar Mirosavljević|Petar]] as Prince of Hum. Petar exiled Andrija and Miroslav's widow (the sister of [[Ban Kulin]] of Bosnia), and Andrija fled to |

[[Andrija Mirosavljević]] was entitled to the governance of Hum, as the heir of [[Miroslav of Hum]], the uncle of Stefan II, but the Hum nobles chose his brother [[Petar Mirosavljević|Petar]] as Prince of Hum. Petar exiled Andrija and Miroslav's widow (the sister of [[Ban Kulin]] of Bosnia), and Andrija fled to Serbia, to the court of Stefan II. In the meantime, Petar fought successfully with neighbouring Bosnia and Croatia. Stefan sided with Andrija and went to war and secured Hum and [[Popovo field]] for Andrija sometime after his accession. Petar was defeated and crossed the Neretva, continuing to rule the west and north of the Neretva, which had in 1203 been briefly occupied by [[Andrew II of Hungary]]. Stefan gave the titular and supreme rule of Hum to his son Radoslav, while Andrija held the district of Popovo with the coastal lands of Hum, including [[Ston]]. By agreement, when Radoslav died, the lands were bound to Andrija.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=53}} |

||

Đorđe of Zeta, in order to secure his lands from Stefan, accepted Venetian suzerainty, possibly in 1208. Đorđe may have done this due to tensions between the two, although this must not be the case. Venice, after the [[Fourth Crusade]], tried to exert control of the Dalmatian ports, and managed in 1205 to submit [[Ragusa (Croatia)|Ragusa]] – Đorđe submitted to prevent that Venice claimed his ports of southern Dalmatia.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=50}} |

Đorđe of Zeta, in order to secure his lands from Stefan, accepted Venetian suzerainty, possibly in 1208. Đorđe may have done this due to tensions between the two, although this must not be the case. Venice, after the [[Fourth Crusade]], tried to exert control of the Dalmatian ports, and managed in 1205 to submit [[Ragusa (Croatia)|Ragusa]] – Đorđe submitted to prevent that Venice claimed his ports of southern Dalmatia.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=50}} |

||

| Line 72: | Line 73: | ||

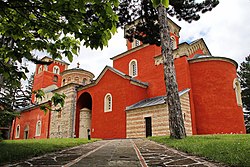

[[File:Manastir Žiča.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Žiča|Žiča monastery]] in [[Kraljevo]] was founded by Stefan]] |

[[File:Manastir Žiča.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Žiča|Žiča monastery]] in [[Kraljevo]] was founded by Stefan]] |

||

Đorđe promised Venice military aid in case of a revolt by another theoretical Venetian vassal, [[Demetrio Progoni|Dhimitër Progoni]], the ''[[Principality of Arbanon|Prince of Albania]] and'' ''Lord of [[Kruja]]''.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=50}} This was likely related to the |

Đorđe promised Venice military aid in case of a revolt by another theoretical Venetian vassal, [[Demetrio Progoni|Dhimitër Progoni]], the ''[[Principality of Arbanon|Prince of Albania]] and'' ''Lord of [[Kruja]]''.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=50}} This was likely related to the Serbia-Zeta conflict.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=50}} Stefan II married off his daughter,{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=50}} [[Komnena Nemanjić|Komnena]], to prince [[Demetrio Progoni|Dhimitër Progoni]] in 1208.{{sfn|Ducellier|1999|p=786}} The marriage resulted in close ties and an alliance between Stefan and Dimitri amidst these conflicts.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=50}}{{sfn|Ducellier|1999|p=786}} Kruja is conquered by [[Despotate of Epirus|Epirote Despot]] [[Michael I Komnenos Doukas]], and Dimitri is not heard of in any surviving sources.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=68}}{{sfn|Ducellier|1999|p=786}} After Dhimitër's death, the lands are left to Komnena,{{sfn|Nicol|1984|p=48}} who soon married [[Greeks in Albania|Greek-Albanian]] [[Gregorios Kamonas]], who took power of [[Krujë|Kruja]],{{sfn|Nicol|1984|p=156}} strengthening relations with Serbia, which had after a Serbian assault on [[Shkodër|Scutari]] been weakened.{{sfn|Nicol|1984|p=156}}{{sfn|Ducellier|1999|p=786}} Đorđe disappears from sources, and Stefan II controls Zeta by 1216, probably through military action.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=50}} Stefan either put Zeta under his personal rule, or assigned it to his son [[Stefan Radoslav]]. Zeta would from now on have no special status, and would be given to the heir apparent.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=50}} |

||

Despot Michael I of Epirus conquered [[Skadar]], and tried to press beyond, but was stopped by the Serbs and his murder by one of his servants in 1214 or 1215.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=68}} He was succeeded by his half-brother [[Theodore Komnenos Doukas]].{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=68}} Theodore took on a policy of aggressive expansion, and allied himself with Stefan II. [[Stefan Radoslav]] married [[Anna Angelina Komnene Doukaina]], the daughter of Theodore.{{sfn|Polemis|1968|p=93}}{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=136}} |

Despot Michael I of Epirus conquered [[Skadar]], and tried to press beyond, but was stopped by the Serbs and his murder by one of his servants in 1214 or 1215.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=68}} He was succeeded by his half-brother [[Theodore Komnenos Doukas]].{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=68}} Theodore took on a policy of aggressive expansion, and allied himself with Stefan II. [[Stefan Radoslav]] married [[Anna Angelina Komnene Doukaina]], the daughter of Theodore.{{sfn|Polemis|1968|p=93}}{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=136}} |

||

| Line 79: | Line 80: | ||

{{main|Coronation of the Serbian monarch}} |

{{main|Coronation of the Serbian monarch}} |

||

Having long wanted to call himself king, Stefan set about procuring a royal crown from the papacy. It is not clear what Stefan promised in regard to the status of the Catholic Church, which had numerous adherents in the western and coastal parts of his realm, but a papal legate finally arrived in 1217 and crowned Stefan. In 1217 Stefan Nemanjić declared his independence from Byzantium and was crowned as king, adopting the title: ''"Crowned King and Autocrat of all Serbian and coastal lands"''.{{sfn|Ćirković|2004|p=39}} The influence of the Catholic Church in Serbia did not last long but angered Serbian clergy. Many opposed Stefan's coronation, with Sava protesting by leaving Serbia and returning to Mount Athos. Later Serbian churchmen were also bothered by Stefan's relations with the papacy; while Stefan and Sava's contemporary [[Domentian]] wrote that the coronation was performed by a papal legate, a century later [[Theodosius the Hilandarian]] claimed that Stefan was crowned by Sava. The contradiction led some Serbian historians to conclude that Stefan underwent two coronations, first by the legate and in 1219 by Sava, but modern scholars tend to agree that only the former took place.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=116}}{{sfn|Ferjančić|Maksimović|2014|pp=37–54}} |

Having long wanted to call himself king, Stefan set about procuring a royal crown from the papacy. It is not clear what Stefan promised in regard to the status of the Catholic Church, which had numerous adherents in the western and coastal parts of his realm, but a papal legate finally arrived in 1217 and crowned Stefan. In 1217 Stefan Nemanjić declared his independence from Byzantium and was crowned as king, adopting the title: ''"Crowned King and Autocrat of all Serbian and coastal lands"''.{{sfn|Ćirković|2004|p=39}} The influence of the Catholic Church in Serbia did not last long but angered Serbian clergy. Many opposed Stefan's coronation, with Sava protesting by leaving Serbia and returning to Mount Athos. Later Serbian churchmen were also bothered by Stefan's relations with the papacy; while Stefan and Sava's contemporary [[Domentian]] wrote that the coronation was performed by a papal legate, a century later [[Theodosius the Hilandarian]] claimed that Stefan was crowned by Sava. The contradiction led some Serbian historians to conclude that Stefan underwent two coronations, first by the legate and in 1219 by Sava, but modern scholars tend to agree that only the former took place.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=116}}{{sfn|Ferjančić|Maksimović|2014|pp=37–54}} |

||

The disagreements surrounding Stefan's coronation were definitively resolved in 2018 by finding evidences that the papal legate never came to Serbia and that Stefan was actually crowned by his brother Sava in 1219.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.eparhija-prizren.org/marko-pejkovic-milan-bojic1-sveti-stefan-prvovencani-nije-dobio-kraljevsku-krunu-iz-rima/ |title=Марко Пејковић, Милан Бојић: Свети Стефан Првовенчани није добио краљевску круну из Рима[1] – ЕПАРХИЈА РАШКО-ПРИЗРЕНСКА У ЕГЗИЛУ|trans-title=Marko Pejković, Milan Bojić: Saint Stephen the First Crowned did not receive the royal crown from Rome }}</ref>{{Unreliable source?|certain=y|reason=author is heavily biased towards eparchy in exile|date=November 2023}} |

|||

==Marriage, monastic vows, and death== |

==Marriage, monastic vows, and death== |

||

| Line 86: | Line 89: | ||

* ''King'' [[Stefan Vladislav I]], ruled 1233–1243 |

* ''King'' [[Stefan Vladislav I]], ruled 1233–1243 |

||

* ''Archbishop'' [[Sava II]] (born ''Predislav'', proclaimed [[Serbian saints|Saint]]) |

* ''Archbishop'' [[Sava II]] (born ''Predislav'', proclaimed [[Serbian saints|Saint]]) |

||

* '' |

* ''Princess'' [[Komnena Nemanjić]], Grand Duchess of [[Kruja]] |

||

Stefan remarried in 1207/1208, his second wife was [[Anna Dandolo]], granddaughter of Venetian doge [[Enrico Dandolo]]. They had one son and one daughter: |

Stefan remarried in 1207/1208, his second wife was [[Anna Dandolo]], granddaughter of Venetian doge [[Enrico Dandolo]]. They had one son and one daughter: |

||

| Line 98: | Line 101: | ||

==In fiction== |

==In fiction== |

||

* The 2017 television series ''Nemanjići |

* The 2017 television series ''Nemanjići – rađanje kraljevine'' (''Nemanjić Dynasty – Birth of a Kingdom'') features him as the main protagonist.{{sfn|Šentevska|2018|pp=343–361}} |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 105: | Line 108: | ||

== References == |

== References == |

||

{{reflist |

{{reflist}} |

||

==Sources== |

==Sources== |

||

| Line 115: | Line 118: | ||

* {{Cite book|last=Curta|first=Florin|author-link=Florin Curta|title=Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1300)|year=2019|location=Leiden and Boston|publisher=Brill|isbn=9789004395190|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-sqiDwAAQBAJ}} |

* {{Cite book|last=Curta|first=Florin|author-link=Florin Curta|title=Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1300)|year=2019|location=Leiden and Boston|publisher=Brill|isbn=9789004395190|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-sqiDwAAQBAJ}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Ducellier|first=Alain|chapter=Albania, Serbia and Bulgaria|title=The New Cambridge Medieval History|volume=5|year=1999|location=Cambridge|publisher=Cambridge University Press|pages=779–795|isbn=9780521362894|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bclfdU_2lesC&pg=PA779}} |

* {{Cite book|last=Ducellier|first=Alain|chapter=Albania, Serbia and Bulgaria|title=The New Cambridge Medieval History|volume=5|year=1999|location=Cambridge|publisher=Cambridge University Press|pages=779–795|isbn=9780521362894|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bclfdU_2lesC&pg=PA779}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Ducellier|first=Alain|chapter=Balkan Powers: Albania, Serbia and Bulgaria ( |

* {{Cite book|last=Ducellier|first=Alain|chapter=Balkan Powers: Albania, Serbia and Bulgaria (1200–1300)|title=The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c. 500–1492|year=2008|location=Cambridge|publisher=Cambridge University Press|pages=779–802|isbn=9780521832311|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ehh6hiqpaDsC}} |

||

| ⚫ | * {{Cite journal|last1=Ferjančić|first1=Božidar|author-link1=Božidar Ferjančić|last2=Maksimović|first2=Ljubomir|author-link2=Ljubomir Maksimović|title=Sava Nemanjić and Serbia between Epiros and Nicaea|journal=Balcanica|year=2014|issue=45|pages=37–54|doi=10.2298/BALC1445037F|url=http://www.doiserbia.nb.rs/ft.aspx?id=0350-76531445037F|doi-access=free|hdl=21.15107/rcub_dais_12894|hdl-access=free}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Dvornik|first=Francis|author-link=Francis Dvornik|title=The Slavs in European History and Civilization|year=1962|location=New Brunswick|publisher=Rutgers University Press|isbn=9780813507996|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LACpYP-g1y8C}} |

|||

| ⚫ | * {{Cite journal|last1=Ferjančić|first1=Božidar|author-link1=Božidar Ferjančić|last2=Maksimović|first2=Ljubomir|author-link2=Ljubomir Maksimović|title=Sava Nemanjić and Serbia between Epiros and Nicaea|journal=Balcanica|year=2014|issue=45|pages=37–54|doi=10.2298/BALC1445037F|url=http://www.doiserbia.nb.rs/ft.aspx?id=0350-76531445037F}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Fine|first=John Van Antwerp Jr.|author-link=John Van Antwerp Fine Jr.|title=The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest|year=1994|orig-year=1987|location=Ann Arbor, Michigan|publisher=University of Michigan Press|isbn=0472082604|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LvVbRrH1QBgC}} |

* {{Cite book|last=Fine|first=John Van Antwerp Jr.|author-link=John Van Antwerp Fine Jr.|title=The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest|year=1994|orig-year=1987|location=Ann Arbor, Michigan|publisher=University of Michigan Press|isbn=0472082604|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LvVbRrH1QBgC}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Ivanović|first=Miloš|chapter=Serbian Hagiographies on the Warfare and Political Struggles of the Nemanjić Dynasty (from the Twelfth to Fourteenth Century)|title=Reform and Renewal in Medieval East and Central Europe: Politics, Law and Society|year=2019|location=Cluj-Napoca|publisher=Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies|pages=103–129|chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/43289161}} |

* {{Cite book|last=Ivanović|first=Miloš|chapter=Serbian Hagiographies on the Warfare and Political Struggles of the Nemanjić Dynasty (from the Twelfth to Fourteenth Century)|title=Reform and Renewal in Medieval East and Central Europe: Politics, Law and Society|year=2019|location=Cluj-Napoca|publisher=Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies|pages=103–129|chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/43289161}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{cite book |last=Madgearu |first=Alexandru |year=2016 |title=The Asanids: The Political and Military History of the Second Bulgarian Empire, 1185–1280 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-9-004-32501-2 }} |

||

| ⚫ | * {{Cite journal|last=Marjanović-Dušanić|first=Smilja|author-link=Smilja Marjanović-Dušanić|title=Lʹ idéologie monarchique dans les chartes de la dynastie serbe des Némanides (1168–1371): Étude diplomatique|journal= Archiv für Diplomatik: Schriftgeschichte, Siegel- und Wappenkunde|year=2006|volume=52|pages=149–158|doi=10.7788/afd.2006.52.jg.149|s2cid=96483243|url=https://www.vr-elibrary.de/doi/10.7788/afd.2006.52.jg.149}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Jireček|first=Constantin|author-link=Konstantin Jireček|title=Geschichte der Serben|year=1911|volume=1|location=Gotha|publisher=Perthes|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XoVOAQAAMAAJ}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Jireček|first=Constantin|author-link=Konstantin Jireček|title=Geschichte der Serben|year=1918|volume=2|location=Gotha|publisher=Perthes|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=o85DAAAAYAAJ}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Kalić|first=Jovanka|author-link=Jovanka Kalić|title=The First Coronation Churches of Medieval Serbia|journal=Balcanica|year=2017|issue=48|pages=7–18|doi=10.2298/BALC1748007K|url=http://www.doiserbia.nb.rs/ft.aspx?id=0350-76531748007K}} |

|||

| ⚫ | * {{Cite journal|last=Marjanović-Dušanić|first=Smilja|author-link=Smilja Marjanović-Dušanić|title=Lʹ idéologie monarchique dans les chartes de la dynastie serbe des Némanides ( |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Mileusnić|first=Slobodan|title=Medieval Monasteries of Serbia|year=1998|edition=4th|location=Novi Sad|publisher=Prometej|isbn=9788676393701|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Xc1WAAAAMAAJ}} |

* {{Cite book|last=Mileusnić|first=Slobodan|title=Medieval Monasteries of Serbia|year=1998|edition=4th|location=Novi Sad|publisher=Prometej|isbn=9788676393701|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Xc1WAAAAMAAJ}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Nicol|first=Donald M.|author-link=Donald M. Nicol|title=The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages|year=1984|orig-year=1957|edition=2. expanded|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9780521261906|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XIj0FfKto9AC}} |

* {{Cite book|last=Nicol|first=Donald M.|author-link=Donald M. Nicol|title=The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages|year=1984|orig-year=1957|edition=2. expanded|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9780521261906|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XIj0FfKto9AC}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Obolensky|first=Dimitri|author-link=Dimitri Obolensky|title=The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500-1453|year=1974|orig-year=1971|location=London|publisher=Cardinal|isbn=9780351176449|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RlBoAAAAMAAJ}} |

* {{Cite book|last=Obolensky|first=Dimitri|author-link=Dimitri Obolensky|title=The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500-1453|year=1974|orig-year=1971|location=London|publisher=Cardinal|isbn=9780351176449|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RlBoAAAAMAAJ}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Orbini|first=Mauro|author-link=Mauro Orbini|year=1601|title=Il Regno de gli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni|location=Pesaro|publisher=Apresso Girolamo Concordia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Fx3OntcdUkQC}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Орбин|first=Мавро|author-link=Mauro Orbini|year=1968|title=Краљевство Словена|location=Београд|publisher=Српска књижевна задруга|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MduZAAAAIAAJ}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Ostrogorsky|first=George|author-link=George Ostrogorsky|year=1956|title=History of the Byzantine State|location=Oxford|publisher=Basil Blackwell|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Bt0_AAAAYAAJ}} |

* {{Cite book|last=Ostrogorsky|first=George|author-link=George Ostrogorsky|year=1956|title=History of the Byzantine State|location=Oxford|publisher=Basil Blackwell|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Bt0_AAAAYAAJ}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Pavlowitch|first=Stevan K.|author-link=Stevan K. Pavlowitch|title=Serbia: The History behind the Name|year=2002|location=London|publisher=Hurst & Company|isbn=9781850654773|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=w-RuLDaNwbMC}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Polemis|first=Demetrios I.|title=The Doukai: A Contribution to Byzantine Prosopography|year=1968|location=London|publisher=The Athlone Press|isbn=9780485131222|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CwwJAQAAIAAJ}} |

* {{Cite book|last=Polemis|first=Demetrios I.|title=The Doukai: A Contribution to Byzantine Prosopography|year=1968|location=London|publisher=The Athlone Press|isbn=9780485131222|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CwwJAQAAIAAJ}} |

||

* {{Cite journal|last=Popović|first=Svetlana|title=The Serbian Episcopal Sees in the Thirteenth Century|journal=Старинар|year=2002|issue=51: 2001|pages=171–184|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yuAVAQAAMAAJ}} |

* {{Cite journal|last=Popović|first=Svetlana|title=The Serbian Episcopal Sees in the Thirteenth Century|journal=Старинар|year=2002|issue=51: 2001|pages=171–184|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yuAVAQAAMAAJ}} |

||

* {{Cite book| |

* {{Cite book|last=Šentevska|first=Irena|chapter=Populistički podtekst igranog TV programa – serija "Nemanjići – rađanje kraljevine"|title=Mediji, kultura i umetnost u doba populizma|year=2018|location=Beograd|publisher=Institut za pozorište, film, radio i televiziju|pages=343–361|chapter-url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342876880}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last=Šentevska|first=Irena|chapter=Populistički podtekst igranog TV programa - serija "Nemanjići - rađanje kraljevine"|title=Mediji, kultura i umetnost u doba populizma|year=2018|location=Beograd|publisher=Institut za pozorište, film, radio i televiziju|pages=343–361|chapter-url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342876880}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last1=Sedlar|first1=Jean W.|title=East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500|year=1994|location=Seattle|publisher=University of Washington Press|isbn=9780295800646|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4NYTCgAAQBAJ}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|editor-last=Stanković|editor-first=Vlada|title=The Balkans and the Byzantine World before and after the Captures of Constantinople, 1204 and 1453|year=2016|location=Lanham, Maryland|publisher=Lexington Books|isbn=9781498513265|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=avTADAAAQBAJ}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Stephenson|first=Paul|title=Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900-1204|year=2000|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9780521770170|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ILiOI0UgxHoC}} |

* {{Cite book|last=Stephenson|first=Paul|title=Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900-1204|year=2000|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9780521770170|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ILiOI0UgxHoC}} |

||

* {{Cite book|last1=Stojkovski|first1=Boris|last2=Kartalija|first2=Nebojša|chapter=Serbia through the Eyes of Contemporary Western Travelers in the Age of Nemanjić Dynasty ( |

* {{Cite book|last1=Stojkovski|first1=Boris|last2=Kartalija|first2=Nebojša|chapter=Serbia through the Eyes of Contemporary Western Travelers in the Age of Nemanjić Dynasty (1166–1371)|title=Deseti međunarodni interdisciplinarni simpozijum Susret kultura: Zbornik radova|year=2019|location=Novi Sad|publisher=Filozofski fakultet|pages=305–321|chapter-url=http://digitalna.ff.uns.ac.rs/sites/default/files/db/books/978-86-6065-544-0.pdf}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Sweeney |first=James Ross |title=Innocent III, Hungary and the Bulgarian Coronation: A Study in Medieval Papal Diplomacy |journal=Church History |volume=42 |issue=3 |pages=320–334 |year=1973 |doi=10.2307/3164389 |jstor=3164389 |s2cid=162901328 |issn=0009-6407 }} |

|||

{{refend}} |

{{refend}} |

||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{commons category|Stefan the First-Crowned}} |

* {{commons category-inline|Stefan the First-Crowned}} |

||

* {{MLCC |external links=1 |url=http://fmg.ac/Projects/MedLands/SERBIA.htm#_Toc105321918 |title-date= |title= Medieval Lands Project - Serbia|date=}} |

|||

{{s-start}} |

{{s-start}} |

||

{{S-hou|[[Nemanjić dynasty]]||around 1165|24 September|1228}} |

{{S-hou|[[Nemanjić dynasty]]||around 1165|24 September|1228}} |

||

{{s-reg|}} |

{{s-reg|}} |

||

{{succession box|before=[[ |

{{succession box|before=[[Stefan Nemanja]]|title=Grand Prince of Serbia|after=[[Vukan Nemanjić|Vukan]]|years=1196–1202}} |

||

{{succession box|before=Vukan|title=Grand Prince of Serbia|after=<small>title elevated→</small>|years=1204–1217}} |

{{succession box|before=Vukan|title=Grand Prince of Serbia|after=<small>title elevated→</small>|years=1204–1217}} |

||

{{succession box|before=<small>←title elevated</small>|title=[[List of Serbian monarchs|King of Serbia]]|after=[[Stefan Radoslav |

{{succession box|before=<small>←title elevated</small>|title=[[List of Serbian monarchs|King of Serbia]]|after=[[Stefan Radoslav|Radoslav]]|years=1217–1228}} |

||

{{s-end}} |

{{s-end}} |

||

| Line 161: | Line 154: | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nemanjic, Stefan}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nemanjic, Stefan}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:12th-century Serbian monarchs]] |

[[Category:12th-century Serbian monarchs]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:13th-century Serbian writers]] |

[[Category:13th-century Serbian writers]] |

||

[[Category:Eastern Orthodox monarchs]] |

|||

[[Category:Medieval Serbian Orthodox clergy]] |

[[Category:Medieval Serbian Orthodox clergy]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:1228 deaths]] |

[[Category:1228 deaths]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Sebastokrators]] |

[[Category:Sebastokrators]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Ktetors]] |

[[Category:Ktetors]] |

||

[[Category:Founders of Christian monasteries]] |

[[Category:Founders of Christian monasteries]] |

||

| Line 175: | Line 168: | ||

[[Category:Founding monarchs]] |

[[Category:Founding monarchs]] |

||

[[Category:Eastern Orthodox royal saints]] |

[[Category:Eastern Orthodox royal saints]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Revision as of 17:31, 19 June 2024

Stefan Nemanjić Стефан Немањић | |

|---|---|

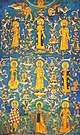

Fresco of Stefan the First-Crowned from Mileševa Monastery | |

| Stefan the First-Crowned | |

| Born | around 1165 |

| Died | 24 September 1228 |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Attributes | Church Builder |

| Grand Prince of Serbia | |

| Reign | 1196–1228 |

| Coronation | 1217 (as king) |

| Predecessor | Stefan Nemanja |

| Successor | Stefan Radoslav |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Eudokia Angelina Anna Dandolo |

| Issue | Stefan Radoslav Stefan Vladislav Stefan Uroš I Sava II Komnena, Grand Duchess of Croia |

| House | Nemanjić dynasty |

| Father | Stefan Nemanja |

| Mother | Anastasija |

| Religion | Serbian Orthodox Christian |

Stefan Nemanjić (Serbian Cyrillic: Стефан Немањић, pronounced [stêfaːn němaɲitɕ]), known as Stefan the First-Crowned (Serbian: Стефан Првовенчани, romanized: Stefan Prvovenčani, pronounced [stêfaːn prʋoʋěntʃaːniː]; c. 1165 – 24 September 1228), was the Grand Prince of Serbia from 1196 and the King of Serbia from 1217 until his death in 1228. He was the first Serbian king by Nemanjić dynasty;[1][2][3][4] due to his transformation of the Serbian Grand Principality into the Kingdom of Serbia and the assistance he provided his brother Saint Sava in establishing the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Early life

Stefan Nemanjić was the second-eldest son of Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja and Anastasija. His older brother and heir apparent, Vukan, ruled over Zeta and the neighbouring provinces (the highest appanage) while his younger brother Rastko (later known as Saint Sava) ruled over Hum.

The Byzantines attacked Serbia in 1191, raiding the banks of the South Morava. Nemanja had a tactical advantage, and began to raid the Byzantine armies. Isaac II Angelos summoned a peace treaty, and the marriage of Nemanja's son Stefan to Eudokia Angelina, the niece of Isaac II, was confirmed. Stefan Nemanjić received the title of sebastokrator.

Conflict over succession

Throughout the 12th century, Serbs were at the center of war events between Byzantium and Hungary for dominance. In such circumstances, Serbs had no chance of gaining independence. Their only chance was to look for an ally on third side.

In 1190, the German Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa drowned in the river Calycadnus. At the same time, Emperor Isaac II Angelos launched a punitive expedition against the Serbs, and Nemanja was defeated in the battle of South Morava. In fact, Constantinople did not want to subdue the Serbs, but to regain Niš and the main road to Belgrade, as well as to make allies of the rebellious Serbs. The peace treaty provided for Stefan Nemanjić, the middle son of the grand zoupan Stefan Nemanja, to marry a Byzantine princess, i.e. niece of the Byzantine emperor.

The concluded peace envisages that the grand zoupan Nemanja will be succeeded by his middle son Stefan, who received the Byzantine title of sebastokrator and the Byzantine princess Eudokia for a wife, and not the firstborn Vukan.

In 1196, at the state assembly near Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Stefan Nemanja abdicated the throne in favor of his middle son Stefan, who became the grand zoupan of Serbia. He left his eldest son Vukan in charge of Zeta, Travunija, Hvosno and Toplica. Nemanja became a monk in his old age and was given the name Simeon. Shortly afterwards, he went to Byzantium, to Mount Athos, where his youngest son Sava had been a monk for some time. They received permission from the Byzantine emperor to rebuild the abandoned Hilandar monastery.

The new Pope Innocent III, who in a letter in 1198 called on the entire West to liberate the Holy Land, was not satisfied with the fact that the Serbs were subordinated to the Patriarch of Constantinople, but wanted to return them to Rome through Vukan. In 1198, the Hungarian dux Andrew conquered Hum (Hercegovina) of grand zoupan Stefan and rebelled against brother king Emeric but did not gain legitimacy from Rome. In any case, the Hungarians became dominant on the eastern Adriatic coast. But Venice, because of its business interests, did not like the eastern coast of the Adriatic to be controlled by the mighty Byzantium or Hungary. Vukan and the Hungarian king Emeric (1196–1204) make an alliance against Stefan, after which a civil war breaks out in Serbia. The action against Stefan was preceded by his letter to the Pope in which he asked for the crown. Around 1200, Stefan expelled his wife Eudokia, a daughter of Alexios III Angelos, who found refuge with Vukan in Zeta. Emeric saw Stefan's move as an open attack on his crown, because in Hungary it was traditionally believed that only it in the region could have primacy with the Roman pope. Stefan lost the conflicts and had to flee the country in 1202 to the ruler of Bulgaria Kaloyan.[5][6][7]

In the meantime, control of the newly formed crusade army was taken over by the powerful Venetian doge Enrico Dandolo, who, to the surprise of all, including the pope himself, in the Fourth Crusade first sent an attack on Hungarian Zara in 1202, and then on Byzantium, whose capital Constantinople crusaders conquered in April 1204. Stefan uses this situation and in the counter-offensive, with the help of Prince Kaloyan, he returns to the throne in Ras in 1204, while Vukan retreats to Zeta. The fighting between the brothers was stopped in 1205 and relations were established as they were before the outbreak of the conflict. Meanwhile, in November 1204, the Hungarian king Emeric died and the Kaloyan of Bulgaria was crowned for king by the Pope.

Numerous states were created on the ruins of Byzantium, which were almost equal in strength. The Crusaders founded the Kingdom of Thessalonica, the principality of Achaia, the duchy of Athens and Thebes, the duchy of Archipelago or Naxos. They were all under rule of Latin emperor of Constantinople. The remaining Byzantine factions also formed their own successor states on the fringes of the empire, at Niceae and Trebizond in Asia Minor, and at Epiros in west Balkan. Of the newly created Greek states, two gained some stability and survived through this period: Niceae under the Laskaris dynasty, which soon became an empire (1208), and Epiros, which took considerably to rise to same status (1224–27). The two rivals sought to present themselves as lawful successor of Empire of the Romans and to get the upper hand in the struggle for its restoration. Bulgaria was located to the north, and Serbia to the northwest. Serbia's neighbors at the time were Epirus to the south, Bulgaria to the east, and the Hungary to the north and west.

Later rule

After the death of Kaloyan, there was a succession war in Bulgaria. Tsar Boril, the most ambitious of the nobles, took the throne and exiled Alexius Slav, Ivan Asen II and Strez (of the Asen family). Strez, the first cousin or brother of Boril, took refuge in Serbia, and was warmly welcomed at the court of Stefan II.[8][9] Even though Boril requested the extradition of Strez to Bulgaria with gifts and bribes, Stefan II refused. Kaloyan had conquered Belgrade, Braničevo, Niš and Prizren, all of which were claimed by Serbia.[8] At the same time, Boril was unable to take military action against Strez and his Serbian patron, as he had suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Latins at Plovdiv.[9] Stefan went as far as to become a blood brother with Strez, in order to assure him of his continued favor.[8]

Andrija Mirosavljević was entitled to the governance of Hum, as the heir of Miroslav of Hum, the uncle of Stefan II, but the Hum nobles chose his brother Petar as Prince of Hum. Petar exiled Andrija and Miroslav's widow (the sister of Ban Kulin of Bosnia), and Andrija fled to Serbia, to the court of Stefan II. In the meantime, Petar fought successfully with neighbouring Bosnia and Croatia. Stefan sided with Andrija and went to war and secured Hum and Popovo field for Andrija sometime after his accession. Petar was defeated and crossed the Neretva, continuing to rule the west and north of the Neretva, which had in 1203 been briefly occupied by Andrew II of Hungary. Stefan gave the titular and supreme rule of Hum to his son Radoslav, while Andrija held the district of Popovo with the coastal lands of Hum, including Ston. By agreement, when Radoslav died, the lands were bound to Andrija.[10]

Đorđe of Zeta, in order to secure his lands from Stefan, accepted Venetian suzerainty, possibly in 1208. Đorđe may have done this due to tensions between the two, although this must not be the case. Venice, after the Fourth Crusade, tried to exert control of the Dalmatian ports, and managed in 1205 to submit Ragusa – Đorđe submitted to prevent that Venice claimed his ports of southern Dalmatia.[11]

Đorđe promised Venice military aid in case of a revolt by another theoretical Venetian vassal, Dhimitër Progoni, the Prince of Albania and Lord of Kruja.[11] This was likely related to the Serbia-Zeta conflict.[11] Stefan II married off his daughter,[11] Komnena, to prince Dhimitër Progoni in 1208.[12] The marriage resulted in close ties and an alliance between Stefan and Dimitri amidst these conflicts.[11][12] Kruja is conquered by Epirote Despot Michael I Komnenos Doukas, and Dimitri is not heard of in any surviving sources.[13][12] After Dhimitër's death, the lands are left to Komnena,[14] who soon married Greek-Albanian Gregorios Kamonas, who took power of Kruja,[15] strengthening relations with Serbia, which had after a Serbian assault on Scutari been weakened.[15][12] Đorđe disappears from sources, and Stefan II controls Zeta by 1216, probably through military action.[11] Stefan either put Zeta under his personal rule, or assigned it to his son Stefan Radoslav. Zeta would from now on have no special status, and would be given to the heir apparent.[11]

Despot Michael I of Epirus conquered Skadar, and tried to press beyond, but was stopped by the Serbs and his murder by one of his servants in 1214 or 1215.[13] He was succeeded by his half-brother Theodore Komnenos Doukas.[13] Theodore took on a policy of aggressive expansion, and allied himself with Stefan II. Stefan Radoslav married Anna Angelina Komnene Doukaina, the daughter of Theodore.[16][17]

Coronation and autocephaly

Having long wanted to call himself king, Stefan set about procuring a royal crown from the papacy. It is not clear what Stefan promised in regard to the status of the Catholic Church, which had numerous adherents in the western and coastal parts of his realm, but a papal legate finally arrived in 1217 and crowned Stefan. In 1217 Stefan Nemanjić declared his independence from Byzantium and was crowned as king, adopting the title: "Crowned King and Autocrat of all Serbian and coastal lands".[18] The influence of the Catholic Church in Serbia did not last long but angered Serbian clergy. Many opposed Stefan's coronation, with Sava protesting by leaving Serbia and returning to Mount Athos. Later Serbian churchmen were also bothered by Stefan's relations with the papacy; while Stefan and Sava's contemporary Domentian wrote that the coronation was performed by a papal legate, a century later Theodosius the Hilandarian claimed that Stefan was crowned by Sava. The contradiction led some Serbian historians to conclude that Stefan underwent two coronations, first by the legate and in 1219 by Sava, but modern scholars tend to agree that only the former took place.[19][20]

The disagreements surrounding Stefan's coronation were definitively resolved in 2018 by finding evidences that the papal legate never came to Serbia and that Stefan was actually crowned by his brother Sava in 1219.[21][unreliable source]

Marriage, monastic vows, and death

Stefan was married, around 1186, to Eudokia Angelina, the youngest daughter of Alexius Angelus and Euphrosyne Doukaina Kamaterina. Eudokia was the niece of the current Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelus. Isaac II arranged the marriage. According to the Greek historian Nicetas Choniates, Stefan and Eudocia quarreled and separated, accusing one another of adultery, after June 1198. They had three sons and two daughters:

- King Stefan Radoslav, ruled 1228–1233

- King Stefan Vladislav I, ruled 1233–1243

- Archbishop Sava II (born Predislav, proclaimed Saint)

- Princess Komnena Nemanjić, Grand Duchess of Kruja

Stefan remarried in 1207/1208, his second wife was Anna Dandolo, granddaughter of Venetian doge Enrico Dandolo. They had one son and one daughter:

- King Stefan Uroš I, ruled 1243–1276

He built many fortresses including Maglič. At the end of his life, Stefan took the monastic vow under the name Symeon and died soon after. He was canonized as his father was.

Legacy

Local tradition, related to the Reževići Monastery claims that it was king Stefan who built (in 1223 or 1226) the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God (Serbian: Црква Успења Пресвете Богородице).

In fiction

- The 2017 television series Nemanjići – rađanje kraljevine (Nemanjić Dynasty – Birth of a Kingdom) features him as the main protagonist.[22]

See also

References

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 38–56.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 33–38.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 389–394.

- ^ Curta 2019, p. 662–664.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 381.

- ^ Sweeney 1973, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Madgearu 2016, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Fine 1994, p. 94.

- ^ a b Curta 2006, p. 385.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fine 1994, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Ducellier 1999, p. 786.

- ^ a b c Fine 1994, p. 68.

- ^ Nicol 1984, p. 48.

- ^ a b Nicol 1984, p. 156.

- ^ Polemis 1968, p. 93.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 136.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 116.

- ^ Ferjančić & Maksimović 2014, pp. 37–54.

- ^ "Марко Пејковић, Милан Бојић: Свети Стефан Првовенчани није добио краљевску круну из Рима[1] – ЕПАРХИЈА РАШКО-ПРИЗРЕНСКА У ЕГЗИЛУ" [Marko Pejković, Milan Bojić: Saint Stephen the First Crowned did not receive the royal crown from Rome].

- ^ Šentevska 2018, pp. 343–361.

Sources

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Ćirković, Sima; Korać, Vojislav; Babić, Gordana (1986). Studenica Monastery. Belgrade: Jugoslovenska revija.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521815390.

- Curta, Florin (2019). Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1300). Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004395190.

- Ducellier, Alain (1999). "Albania, Serbia and Bulgaria". The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 779–795. ISBN 9780521362894.

- Ducellier, Alain (2008). "Balkan Powers: Albania, Serbia and Bulgaria (1200–1300)". The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c. 500–1492. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 779–802. ISBN 9780521832311.

- Ferjančić, Božidar; Maksimović, Ljubomir (2014). "Sava Nemanjić and Serbia between Epiros and Nicaea". Balcanica (45): 37–54. doi:10.2298/BALC1445037F. hdl:21.15107/rcub_dais_12894.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Ivanović, Miloš (2019). "Serbian Hagiographies on the Warfare and Political Struggles of the Nemanjić Dynasty (from the Twelfth to Fourteenth Century)". Reform and Renewal in Medieval East and Central Europe: Politics, Law and Society. Cluj-Napoca: Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 103–129.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2016). The Asanids: The Political and Military History of the Second Bulgarian Empire, 1185–1280. BRILL. ISBN 978-9-004-32501-2.

- Marjanović-Dušanić, Smilja (2006). "Lʹ idéologie monarchique dans les chartes de la dynastie serbe des Némanides (1168–1371): Étude diplomatique". Archiv für Diplomatik: Schriftgeschichte, Siegel- und Wappenkunde. 52: 149–158. doi:10.7788/afd.2006.52.jg.149. S2CID 96483243.

- Mileusnić, Slobodan (1998). Medieval Monasteries of Serbia (4th ed.). Novi Sad: Prometej. ISBN 9788676393701.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1984) [1957]. The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages (2. expanded ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521261906.

- Obolensky, Dimitri (1974) [1971]. The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500-1453. London: Cardinal. ISBN 9780351176449.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Polemis, Demetrios I. (1968). The Doukai: A Contribution to Byzantine Prosopography. London: The Athlone Press. ISBN 9780485131222.

- Popović, Svetlana (2002). "The Serbian Episcopal Sees in the Thirteenth Century". Старинар (51: 2001): 171–184.

- Šentevska, Irena (2018). "Populistički podtekst igranog TV programa – serija "Nemanjići – rađanje kraljevine"". Mediji, kultura i umetnost u doba populizma. Beograd: Institut za pozorište, film, radio i televiziju. pp. 343–361.

- Stephenson, Paul (2000). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900-1204. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521770170.

- Stojkovski, Boris; Kartalija, Nebojša (2019). "Serbia through the Eyes of Contemporary Western Travelers in the Age of Nemanjić Dynasty (1166–1371)" (PDF). Deseti međunarodni interdisciplinarni simpozijum Susret kultura: Zbornik radova. Novi Sad: Filozofski fakultet. pp. 305–321.

- Sweeney, James Ross (1973). "Innocent III, Hungary and the Bulgarian Coronation: A Study in Medieval Papal Diplomacy". Church History. 42 (3): 320–334. doi:10.2307/3164389. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3164389. S2CID 162901328.

External links

Media related to Stefan the First-Crowned at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Stefan the First-Crowned at Wikimedia Commons

- 12th-century Serbian monarchs

- 13th-century Serbian monarchs

- 13th-century Serbian writers

- Medieval Serbian Orthodox clergy

- 1160s births

- 1228 deaths

- Sebastokrators

- Ktetors

- Founders of Christian monasteries

- Nemanjić dynasty

- Burials at Serbian Orthodox monasteries and churches

- Founding monarchs

- Eastern Orthodox royal saints